I felt great shame and anger in 2011. It was the first I had ever heard of the Indian Residential Schools in Canada, and I felt that my education system had failed me epically. At the time, I had already been a middle school teacher for 7 years, and the feeling that I had been failing to educate my students about the realities of Indigenous experiences in Canada was upsetting. Every year since then, I have made it a priority to read Fatty Legs with my students, and to spend time discussing the legacy of residential schools beyond that one story.

We have remounted our choral theatre production of Fatty Legs three times since 2011, once for a tour of schools in the Maritimes, and twice for school shows in Ontario. My students have been overwhelmingly supportive of the time I need to take away from my classroom in order to bring this story to other children.

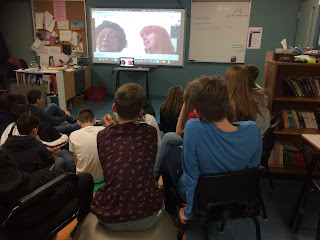

This year, following my two weeks away on tour, we were fortunate enough to be able to organize a Google Hangout with Olemaun and Christy. My grade 8 students took time in advance to prepare questions, and to organize the classroom in a way that would look and feel welcoming over a video chat (we went through several iterations of this, using the projector to gauge how we would look to a viewer - they wanted to avoid looking "intimidating, like we're ganging up on them.")

This year, following my two weeks away on tour, we were fortunate enough to be able to organize a Google Hangout with Olemaun and Christy. My grade 8 students took time in advance to prepare questions, and to organize the classroom in a way that would look and feel welcoming over a video chat (we went through several iterations of this, using the projector to gauge how we would look to a viewer - they wanted to avoid looking "intimidating, like we're ganging up on them.")My students blew me away with their insightful questions, the intentness with which they listened, and their respect for Olemaun's lived experiences. They were kind, they prefaced their questions with some of the reasons why they were asking, they asked follow-up questions that showed they were really listening and reflecting during the conversation. Not all of them, not all of the time, but enough that the flow of the dialogue was natural and did not feel like an interrogation.

Forty-five minutes is barely enough time to scratch the surface of the legacy of residential schools, nor is it adequate for students who are speaking with an elder from a First Nations community (most of them for the first time). Afterwards, I asked students to reflect in writing on what had resonated the most with them in the conversation, and if they had any further questions that had come out of hearing the perspectives offered by Olemaun and Christy.

Below are some of the highlights. Some students chose not to respond to the writing prompt (this is always their right during our writing periods), but many did, and what they had to say revealed significant understanding and reflection.

No comments:

Post a Comment